In 2022, MNCH archaeologists and researchers conducted a data recovery project for the Oregon Department of Transportation to investigate an archaeological site on the east side of the 1913 Van Buren Bridge in Corvallis. The research is part of a plan to build a new earthquake-ready bridge in the same location.

Corvallis used the area under the bridge on the east side of the river as a community dump site between 1910 and 1913.

The site has potential to provide unique and significant information about the ethnicity, demographics, businesses, household practices, and trash disposal methods of Corvallis during a narrow window of time in the early twentieth century.

For more information, visit the Oregon Department of Transportation's project page.

Modern-day Corvallis stands on the traditional homelands of the Mary’s River or Ampinefu Band of Kalapuya. Following the Willamette Valley Treaty of 1855, Kalapuya people were forcibly removed to reservations in Western Oregon. Living descendants of these people are a part of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon and the Confederated Tribes of the Siletz Indians.

The Van Buren Bridge replaced a ferry service that originally connected the towns of Marysville (later called Corvallis) and Orleans beginning in 1848. Orleans, which was on the lower riverbank, was essentially swept away during floods in the winter of 1861-1862. The ferry continued operating after the devastating flood up until 1913, when construction on Van Buren bridge was complete.

For much of the nineteenth century, trash disposal was an unregulated affair. Newspaper articles published in the Corvallis Gazette-Times note that "filth, dirt, and refuse matter" in the alleys of town "until it makes the nastyest [sic] most foul and filthy cespool [sic] that the human imagination can think of" (15 December 1882, p. 2).

By 1910, Corvallis secured a dumping site on the east side of the Willamette River, it was short-lived, however, as the Van Buren Bridge opened on the location in 1913, and the dumping of anything other than "clean" fill, such as construction materials and metal cans, was prohibited.

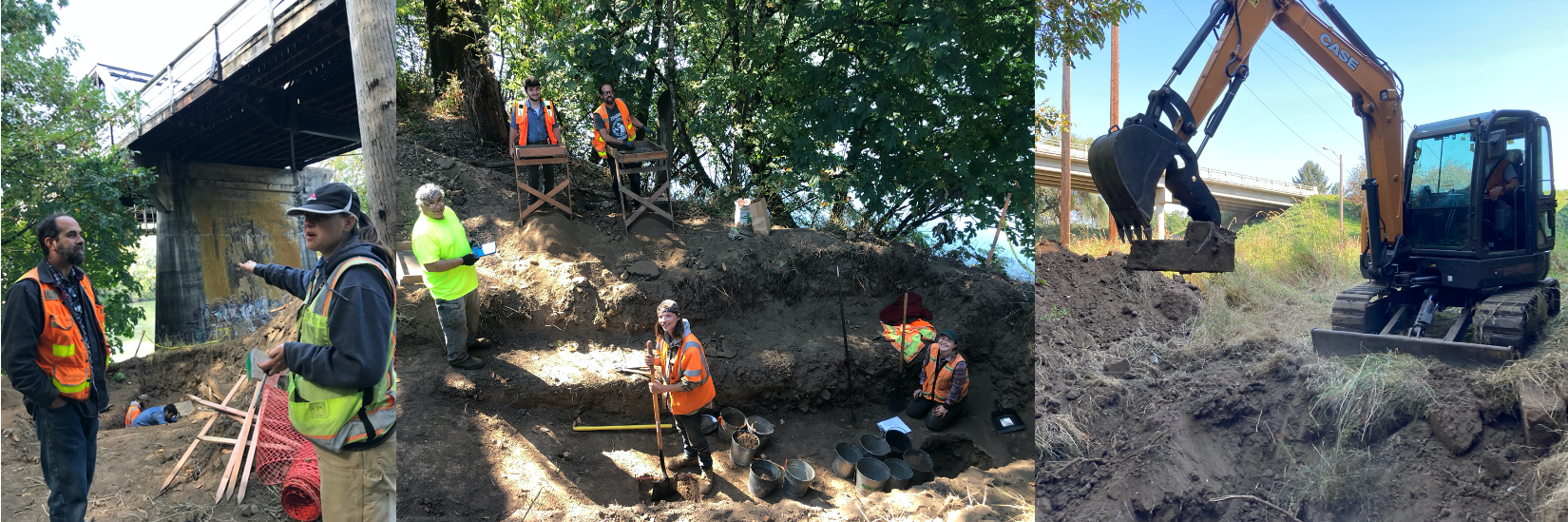

The site continued as a dump site for construction materials and any other "clean" waste for many years after the community dump closed down, and fill was placed on top of the site in order to stabilize the bank underneath the Van Buren Bridge. The researchers' first task was to use an earth mover to clear construction debris and dig down deep enough to get to the historic dump.

Then the data recovery could begin in earnest. On a project like this, researchers conduct methodical hand excavations in strategic locations, collecting meticulous data throughout the site. They collect all human-made items, but also collect information on soil composition, relative age of anything they find, and how much and what kind of items they find. They also map the site for any future work that anyone might do on the area.

After two to three weeks in the field, the team brought the items to the museum for cleaning and study.

Click on any photo below to enlarge.

A badge prior to cleaning. | |

Stratigraphy of one of the trenches. | |

Archaeologist Marlene Jampolsky surveys in the Willamette river. | |

A painted doll's eye in the field. | |

In the lab, archaeologists are cleaning and cataloging all the items recovered from the site. | |

Some items can be identified using historical documents like catalogs of products from the time period. | |

This cast iron stove top is currently undergoing cleaning in an electrolysis tank. |

After items have been cleaned, archaeologists begin cataloguing and identifying the objects as best they can. Here are some notable finds.

These ceramic vessel fragments were found in three different trenches. It's unclear if they are all from the same household; transfer print patterns on ceramics were popular in the western United States in the late 1800s. Archaeologists identify the pattern on these fragments as the "Abbey" pattern from George Jones & Sons, manufactured between 1901 and the 1920s. | |

This bone handle, dating to the early 1900s, likely belonged to a shaving cream or lather brush from a men's shaving kit. Lather brushes were made with a variety of handle types -- bone, antler or horn, or wood or metal covered in enamel for a smooth finish. They were shaped for easy holding and would have had animal hair bristles. |

Why are we digging here?

The Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT), in partnership with the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), proposes to build a new two-lane bridge over the Willamette River on OR34 (the Corvallis-Lebanon Highway). The river divides Benton and Linn counties; the west (Benton County) side of the river is occupied by the City of Corvallis. The new bridge would replace the existing Van Buren Bridge, built in 1913. The new bridge will reduce annual maintenance costs, increase reliability of motor vehicle traffic crossing the Willamette River during seismic or flooding events, and improve overall safety for pedestrians, bicyclists, and motor vehicles.

What are we digging for?

This location was the former dump site for the city of Corvallis, concentrated use of which occurred from 1910 to 1913. It was partially discontinued in 1913 when the Van Buren Bridge was opened, after which time only “clean fill” such as structural materials, gravel, and soil were allowed to be dumped here. The dump seems to have been abandoned by 1916. This city dump was among the first dumps specifically designated by the city as a place to deposit community garbage and was one in a series of short-term city dump locations used through most of the 1920s.

This location was also next to the ferry landing at the townsite of Orleans. The town was established in 1951 and competed with Corvallis for river trade until a big flood in the winter of 1861 swept the town away. Residents of Orleans either moved to Corvallis or to higher ground several miles to the east.

When was the bridge built?

The existing Van Buren Bridge was opened on March 11, 1913, called the Willamette River Bridge. The Coast Bridge Company constructed the Van Buren Street Bridge in 1913 for Benton County. The bridge replaced the ferry that had been in use since the 1860s to connect Corvallis to Linn County and the Willamette Valley. Later, the mechanism to operate the swing span was removed or disabled.

The Van Buren Bridge is significant in the area of Engineering because of its distinctive center pivot swing span and pin-connected steel truss members. These bridge engineering features are relatively rare now because, over the course of the 20th Century, they were superseded by other materials and techniques, such as the shift from steel highway bridges to concrete. The pins in pin-connected bridges were essentially large bolts that held the truss members together. Unfortunately, vibrations from traffic and age tend to loosen pin connections. After about 1915, riveted joints with their superior rigidity became the standard means of connecting steel truss bridge members.

Pin connected trusses are a rare and obsolete technology, with only 20 examples of pin connected trusses in Oregon. The Van Buren Bridge is the only pin connected moveable bridge in Oregon. The bridge is not only Oregon’s only remaining example of a movable bridge built with rare pin-connection technology, but also the only example west of the Mississippi.

What triggered the archaeological excavation?

The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (NHPA) Section 106 requires that each federal agency identify and assess the effects its actions may have on historic resources. Under Section 106, each federal agency must consider public views and concerns about historic preservation issues when making final project decisions. It was determined that the Corvallis Dump Site underneath the east side of the Van Buren Bridge was a significant archaeological resource, and the decision was made to conduct archaeological investigations as part of mitigation on the impact to the resource construction of the new bridge will cause.

What is so important about an old dump site?

The site has the potential to provide unique and significant information about the ethnicity, demographics, businesses, household practices, and trash disposal methods of Corvallis during a narrow window of time in the early twentieth century. Previous floods and fires have destroyed portions of the historical record, so the recovery of information archaeologically can fill in the gaps of Corvallis history.

Cowan et al. (2021) encountered more than a meter of sterile sand and angular gravel fill over the presumed site area east of their excavation units, which their shovel tests probes were not able to penetrate. We proposed to mechanically remove the fill material in trenches extending east from the bank edge. It is estimated that trenches will be about four meters wide, ca.15 m long, and approximately a meter deep to expose the sub-fill surface. The trench width is necessary to allow excavation from the exposed original surface to depths of a meter or more, thus maintaining a stepped excavation within OSHA safety standards. This would permit an up to 2 m wide work surface starting below the fill and beginning on the presumed surface of the cultural deposit.

- What are the horizontal and vertical site limits? Can in situ vs. transported site materials be systematically distinguished? Can dump episodes or sequences be delineated so that analytical units within the dump can be identified?

- Site 35LIN842 is in the vicinity of the ferry terminal at the Orleans townsite; are there historic-period artifacts in the site area that can be potentially associated with the occupation of Orleans (ca. 1851-1862), or operation of the ferry (1848-1913), rather than the Van Buren dump (ca. 1910-1913)?

- What can the artifacts reveal regarding economic and social status, and ethnic diversity, of the households and businesses of the 1910-1913 Corvallis community?

- What does the assemblage reveal about the Corvallis community’s engagement with local vs. remote sources for consumer goods?